Despite her reputation as England’s greatest and most popular monarch, Elizabeth’s reign was a turbulent one, and she was the target of an almost constant series of rebellions and conspiracies to drive her from the throne. The key political issue of the time was the legitimacy of the sovereign, but the Tudor dynasty had no unquestioned right to rule; its founder, Henry VII, was himself a usurper with only a dubious claim to the throne.

HENRY VIII’S TANGLED SUCCESSION

Much of Elizabeth’s reign was shaped by the circumstances of her birth. She was the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, Henry’s second wife. She was born in 1533, five months after Henry, having broken with the Pope and the Catholic Church, declared his marriage to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, was invalid.when her mother was executed three years later, Elizabeth herself was declared illegitimate. When Henry’s third wife, Jane Seymour, gave birth to a son, Edward, in 1537, he became Henry’s heir. An Act of Succession in 1543, confirmed by Henry’s will, declared that if Edward died without heirs, the throne would pass first to Elizabeth’s half-sister Mary Tudor, daughter of Henry’s first wife, and then to Elizabeth.

EDWARD AND PROTESTANTISM

After Henry died, Edward succeeded him. His father had quarreled with papal authority rather than Catholic theology, but Edward VI turned the Church of England into a reformed, Protestant church shaped by Calvinist doctrine. His early death, in 1553, created a brief crisis of succession. Protestants led by the Duke of Northumberland tried to head off a return to Catholicism by crowning the Protestant Lady Jane Grey instead of Mary Tudor, who had remained a staunch Catholic. Lady Jane reigned for nine days before Mary’s supporters deposed her, and both she and Northumberland paid with their heads.

“BLOODY MARY”

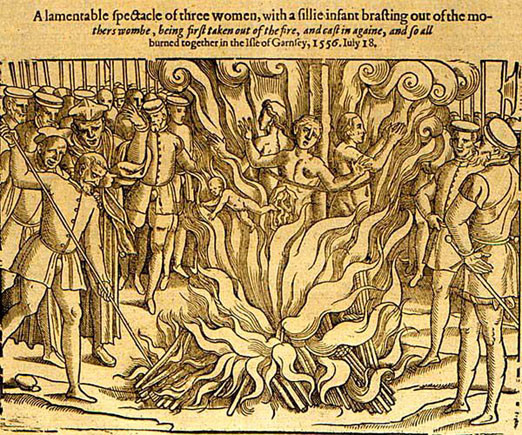

Queen Mary’s reign was disastrous. Her sole objective was to restore the old, Catholic, faith by savagely repressing the new. Three hundred of her subjects, from bishops to villagers, were burned at the stake for refusing to renounce their Protestant beliefs. Hundreds more fled to the continent. For the oppressed reformers, the Protestant Elizabeth was a beacon of hope; to Mary she was a threat. To prevent the succession of the much-younger Elizabeth, Mary had to marry and produce an heir. Her plan to marry the Catholic Prince Philip of Spain, however, outraged the nation, and Sir Thomas Wyatt, son of the poet, led a rising in the south that reached the city of London.

When it failed, Mary dispatched Elizabeth to the Tower; she had the conspirators tortured to provide evidence of Elizabeth’s involvement in the rising. But none was found, and Elizabeth was sent off to house arrest. Mary’s marriage to Philip proved a barren one, and Mary died in 1558 without producing a Catholic heir.

QUEEN ELIZABETH

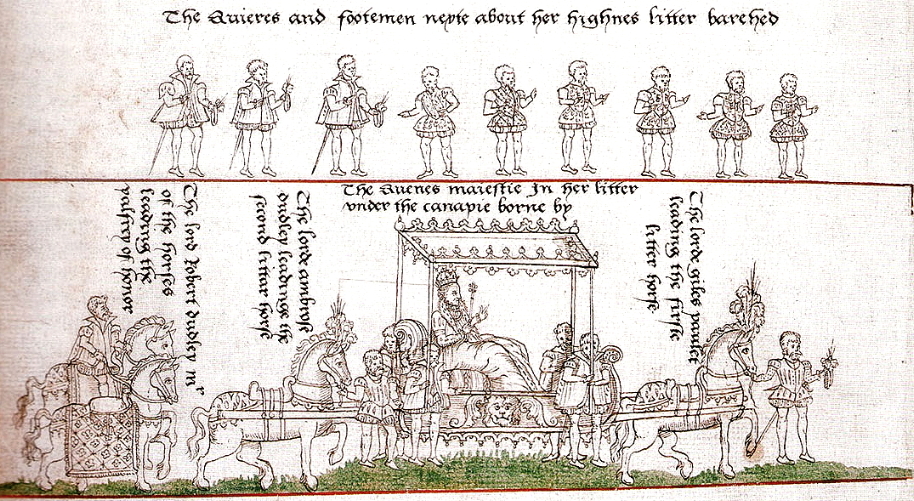

The Spanish ambassador was outraged by the “indecent rejoicings” over Mary’s death. At her coronation Elizabeth kissed an English translation of the Bible, a book that Mary had banned. An Act of Uniformity (1559) restored the Protestant prayer book and service, and Elizabeth made herself “Supreme governor” of an English church freed again from the Church of Rome. In 1559 Elizabeth’s first Parliament formally urged her to marry, to produce an heir and settle the question of who would succeed her. But while she entertained suitors both from England and abroad, she steadily refused to beget an heir or name her successor.

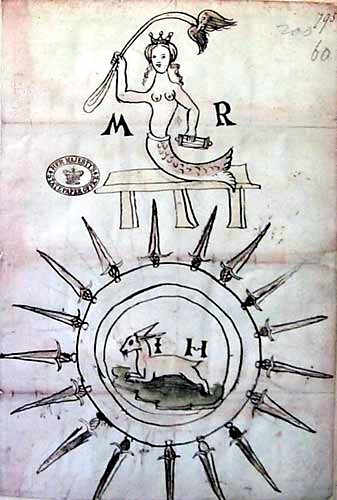

MARY, QUEEN OF SCOTS, AND THE CATHOLIC OPPOSITION

The question of who would succeed Elizabeth dominated her reign, influencing her attitude towards marriage and religion. In the early years of Elizabeth’s reign, conspiracies to restore Catholicism and replace Elizabeth with the Catholic Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, flourished. In 1568, Mary, who had hastily married one of the assassins of her husband, was driven from her country by her subjects. She fled to England, where she demanded her cousin Elizabeth’s protection and help in recovering her crown. As Henry VII’s great-granddaughter, Mary’s claim to the English throne was perhaps stronger than Elizabeth’s. Mary’s father, after all, had never declared her illegitimate. Mary’s presence in England stirred the Catholic lords of the North to rise up on behalf of her and their religion.

THE NORTHERN RISING (1569)

Mary’s secret plan to marry the premier peer of England, Thomas Howard, the fourth Duke of Norfolk, precipitated the rising. The plan was discovered, and Norfolk was imprisoned in the Tower in October. In November his brother-in-law, the Earl of Westmoreland, with the Earl of Northumberland, mustered a rebel army in the northern counties. The rebels, who carried the Catholic banner of the five wounds of Christ, destroyed English bibles and Elizabeth’s Book of Common Prayer, restored traditional altars, and celebrated mass in Durham cathedral. Besides the suppression of the old religion, the earls complained of the Queen’s choice of “divers disordered and evil-disposed persons,” whose “subtle and crafty dealing” had “disordered the realm and now lastly seek the destruction of the nobility.” On November 24 Queen Elizabeth proclaimed them rebels and sent troops under Lord Sussex to suppress the rising. Westmoreland escaped into exile, but Northumberland, who fled to Scotland, was handed back and beheaded. Norfolk promised to abandon his plans to marry Mary and was released.

EXCOMMUNICATION (1570)

In February, 1570, Pope Pius V promulgated a bull, Regnans in Excelsis, excommunicating Elizabeth and freeing her Catholic subjects from their allegiance to a heretical sovereign. The edict made her position infinitely more perilous, since it denied her divine right, God’s sanction of her power. The bull reached England in May, when a bold Catholic hand posted it on the door of the Anglican bishop of London. Elizabeth’s government countered with “An Homily against Disobedience and Willful Rebellion,” a sermon composed to be read in all churches. It made the government’s case against insurrection by justifying all monarchy, deriving the monarch’s absolute rule from God’s first commandment against disobedience to Adam and Eve. (See the selection.) The papal campaign continued. In 1580 Pope Gregory XIII proclaimed that assassinating the great heretic Elizabeth would not constitute a deadly sin. And in 1588, on the eve of the Spanish Armada, Pope Sixtus V excommunicated Elizabeth again, declaring,

First, for that she is an heretic and schismatic, excommunicated by two His Holiness’s predecessors, obstinate in disobedience to God and the See Apostolic, presuming to take upon her, contrary to nature, reason, and all laws both of God and man, supreme jurisdiction and spiritual authority over men’s souls. Secondly for that she is a bastard, conceived and born by incestuous adultery, and therefore uncapable of the kingdom. . . . Thirdly for usurping the Crown without right, having the impediments mentioned, and contrary to the ancient accord made between the See Apostolic and the realm of England. . . that none might be lawful king or queen thereof, without the approbation and consent of the supreme Bishop . . . doth excommunicate, and deprive her of all authority and princely dignity, and of all title and pretension to the said Crown and kingdom of England and Ireland; declaring her to be illegitimate, and an unjust usurper of the same; and absolving the people of those States, and other persons whatsoever, from all obedience, oath, and other band of subjection unto her, or to any other in her name.

THE RIDOLFI PLOT (1571)

In 1571, Roberto Ridolfi, an Italian banker who had already been questioned by English authorities after the Northern Rising, began to plot Mary’s escape and marriage to Norfolk with the contrivance of Norfolk, the Spanish ambassador, and the Pope. A more dangerous intrigue, the Ridolfi Plot called for Spain to intervene with troops to support the marriage and put Mary on the throne. Its discovery by Elizabeth’s agents brought Norfolk to the block and fatally tainted Mary’s cause. But it did not stop her incessant intrigues.

THE THROCKMORTON PLOT (1583)

In 1583, Francis Throckmorton, a Catholic acting as a go-between for Mary and Mendoza, the Spanish ambassador, was arrested, and a list of Catholic conspirators and details of ports to be used in a possible invasion were found. Under torture Throckmorton confessed to a conspiracy to murder Elizabeth and put Mary on the throne again with the help of foreign troops, led by the French Henri, duc de Guise. Throckmorton was executed at Tyburn. Mendoza was expelled and left threatening to return with an army. Panicky Londoners knelt in the streets to give thanks for the Queen’s delivery, and the Privy Council, her executive body, convinced Parliament to pass the Bond of Association in 1584, calling on all Englishmen to take an oath to seek out and kill anyone plotting to murder the Queen.

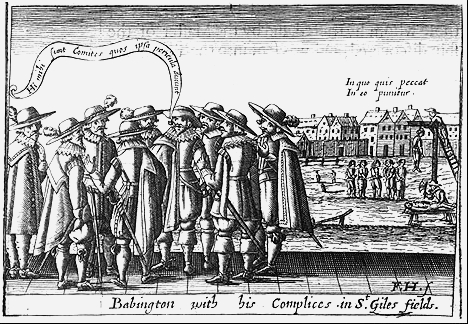

THE BABINGTON PLOT (1586)

In 1586 Mary’s Catholic page, Anthony Babington, was enlisted by John Ballard, a Catholic priest, in a plot to murder Elizabeth and, with help again from agents of Spain and the Pope, to release Mary from captivity. “In the month of July,” John Stow wrote in his Chronicles, “divers traitorous persons were . . . detected of a most wicked conspiracy against her Majesty, and also of minding to have stirred up a general rebellion throughout the whole Realm. For joy of whose apprehension, the Citizens of London . . . caused the bells to be rung, and bonfires to be made, and also banqueted every man according to his ability, some in their houses, some in the streets.” The unfortunate Babington had unknowingly recruited one of Elizabeth’s agents to pass messages from Mary to the French ambassador.

The discovery of those messages, hidden in a beer barrel, along with the Stafford plot of 1587 to blow up Elizabeth by putting gunpowder under her bed, finally convinced Elizabeth that she would not be safe as long as Mary lived. “You have planned in divers ways and manners to take my life and to ruin my kingdom,” she wrote to Mary in October. After great hesitation, she sent Mary to the block in 1587. News of her death was met in London with more bonfires, bells, and feasting. A volume entitled Verses of Praise and Joy, Written upon her Majesty’s Preservation, appeared in 1586. It containied “Tichborn’s Lamentation,” supposedly written by one of the conspirators awaiting execution in the Tower; the “Lamentation” became one of the most popular poems of the age.

THE LOPEZ PLOT (1594)

Mary’s beheading and the defeat of the Spanish Armada in the following year—“the power of God having wonderfully overcome them,” Stow wrote—did not stop the plotting. In 1594, Roderigo Lopez, a Jewish-Portuguese doctor whose position as the Queen’s personal physician put him at the center of court intrigue, was accused by the Earl of Essex of having conspired with Spanish emissaries to poison the Queen. Despite his protestations of innocence the Queen signed his death warrant, and he was hanged, drawn, and quartered before a jeering London mob. The hostility stirred up against Lopez spawned a number of comically villainous Jews on the stage, perhaps including Shakespeare’s Shylock.

THE LAST YEARS: RIOT AND DISORDER

The last decade of Elizabeth’s reign, 1593–1603, was not the golden age of legend. Wars, famine, and pestilence, horsemen of the apocalypse, struck virtually at once. War with Spain in the Netherlands and France and later the rebellion in Ireland forced Elizabeth to levy crippling taxes on the entire nation. Bubonic plague—the Black Death—struck in 1592; the theaters were closed between June, 1592, and May, 1594, and 10,675 Londoners died of the plague in 1593 alone. Bad harvests each year from 1594 to 1597 drove up the price of food. Dearth and high taxes led to riots in London in 1595, Somerset in 1596, and Kent, Norfolk, and Suffolk in 1597; the Somerset rioters said “they were as good to be slain in the marketplace, as starve in their own houses!” In Parliament in 1597, Elizabeth’s most trusted advisor, William Cecil, Lord Burghley, acknowledged “the lamentable cry of the poor who are likely to perish by means . . . of the dearness and high price of corn.” The commoners resented the lucrative monopolies on household goods, like salt and starch, and customs duties on imports and exports, like wine and cloth, that the Queen used to reward her favorites. In 1601 Parliament prevailed upon her to roll back some of the more burdensome monopolies. But the nation was growing tired of its Queen.

OPPOSITION WITHIN THE COURT: THE ESSEX REBELLION

Amid the aristocracy at court opposition was growing as well. Elizabeth relied more and more on a small clique of advisors; the Cecils, father and son, controlled the Privy Council and the Exchequer or treasury. Meanwhile, those on the outs coalesced around the dashing figure of Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex.

In the later fifteen-eighties, Essex, then in his early twenties, became the favorite of the Queen, thirty years his elder. Essex, who had been knighted for gallantry in the campaign to aid the Dutch revolt against Spain in 1586, became Elizabeth’s master of horse in 1587 and was given the Order of the Garter, the oldest and highest of honors, in 1588. In May, 1587, a courtier reported, the Queen often had “nobody with her but my Lord of Essex; and at night my Lord is at cards, or new game or another with her, that he cometh not to his own lodgings till birds sing in the morning.” In 1593 Elizabeth appointed him to the Privy Council, the work horse of Tudor government staffed by her most trusted counselors. In 1596 he led a force that sacked the Spanish port of Cadiz and returned home a hero, his popularity threatening to eclipse that of the Queen.

But Elizabeth herself, as Essex’s own protege Francis Bacon warned him, favored a policy of peace and, like Shakespeare’s Richard II, distrusted Essex’s standing with the commons:

As were our England in reversion his, And he our subjects’ next degree in hope. (Richard II, 1.4.35–6)

She rejected Essex’s policies and blocked the advancement of supporters like Bacon. By 1597, spurning the language of amorous compliment that ambitious courtiers directed at the Queen, Essex lamented the fickleness of women in a poem reflecting his fall from the Queen’s favor:

Whilst she lov’d thee best a while, See how she hath still delayed thee: Using shows for to beguile, Those vain hopes that have deceiv’d thee.

In July 1598, during a bitter quarrel over the appointment of a new deputy for Ireland, the volatile Essex exploded, yelling at the aged Queen that her decisions “were as crooked as her carcass” and insolently turning his back on her. When the enraged Queen boxed his ears, he went for his sword and had to be restrained.

Thereafter relations between them were strained. Essex got his last chance for preferment in 1599 when Elizabeth named him to head an army to crush a revolt in Ireland. Cheering throngs crowded the streets to see him off, Stow wrote in his Chronicles, “for more than four miles’ space, crying and singing, ‘God bless your Lordship,’ ‘God preserve your Honor.’” Shakespeare himself caught the mood of the nation in Henry V:

Were now the general of our gracious empress, As in good time he may, from Ireland coming, Bringing rebellion broached on his sword, How many would the peaceful city quit, To welcome him! (Henry 5. Prologue, 30–4)

But the campaign failed. Bogged down in Ireland, Essex arranged an ignoble truce, abandoned his post, and dashed back to court in defiance of his orders, throwing himself at the Queen’s feet in her bedchamber in Nonsuch Castle. “Perilous and contemptible,” the Queen called his breach of trust; the next day, she had him entrusted to the Lord Keeper, under house arrest. “Whereat,” Stow reported, “ the people still murmured.” Banished from the royal presence, stripped of his offices and rich leases on customs duties, Essex attracted a band of malcontents, and Essex House became the center of opposition to Elizabeth. Among the disaffected was the Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare’s patron. By January, 1601, their resentment had swelled into a conspiracy involving Southampton, several other earls, a number of highly placed lords, and their followers.

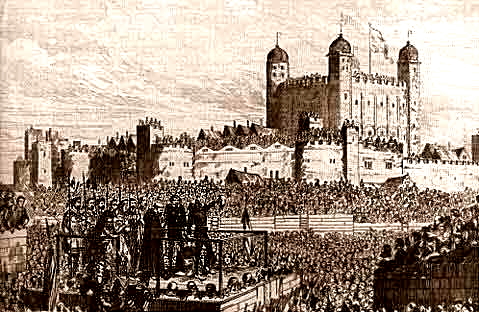

But their plot was discovered, forcing them to act before they were ready. On February 8, 1601, Essex stormed into London with several hundred armed men “very rebelliously to disinherit the Queen of her crown and dignity.” They planned to take the Tower, surprise the court, enter the Queen’s privy chamber, and force her to dismiss her ministers and, perhaps, surrender the crown to Essex. The Queen, “of her abounding mercy,” according to the official account, “sent to see if it were possible to stop rebellion.” But Essex “very treacherously” imprisoned the Lord Keeper, the Controller of Her Majesty’s Household, and the Lord Chief Justice when they “commanded the earls and their adherents very strictly to dissolve their assemblies and to lay down their arms . . . and altogether refused Her Majesty’s authority.” They marched through the city streets, calling on the people to join them. Few did, and Essex retreated to Essex House, where he was taken. Essex and Southampton were tried and sentenced to death. But so many other earls and lords were implicated in Essex’s treason that Elizabeth dared not punish them.

Southampton was reprieved, but Essex, too proud to beg the Queen for his life, was not. On a chilly February morning a nervous executioner needed three strokes to take off the earl’s head. He had reason to be nervous; “the hangman was beaten as he returned” from the Tower, Stow reported, “so that the Sheriffs of London were sent for, to assist and rescue him from such as would have murdered him.” Even in death Essex remained the people’s favorite.

“FROM THE STAGE TO THE STATE”

The many uprisings and plots against Elizabeth’s life suggest how deeply Shakespeare’s history plays reflect the politics of his own time as much as England’s past. The issues of legitimacy and succession, riot and tyranny, and war and rebellion that fill the history plays were the same ones debated at court and in the alehouses, and the plays provided Shakespeare and his audience with a means of discussing those questions of state and religion that the authorities considered seditious when spoken of directly through the glass of historical fiction.

HENRY THE FOURTH AND THE NORTHERN RISING

Shakespeare’s history plays intersect with Elizabethan politics in several ways. The Northern Rising in 1569, scholars conjecture, may have supplied Shakespeare with a model for Henry IV Part I . That rebellion was hatched by descendants of Shakespeare’s Percies and the Earl of Westmoreland, and the Catholic Bishop of Ross played a part like that of Shakespeare’s Archbishop of York. In Shakespeare’s play, the Percies’ resentment over Henry IV’s refusal to ransom Mortimer, the pretender to the throne, and his demand that they surrender Scots prisoners may be patterned after the demands of the Northern lords in 1569 that Mary, the Scots pretender to the throne and Northumberland’s prisoner, be left in the keeping of an Elizabethan Percy. Both rebellions, the rising against Elizabeth and that against Henry IV, reflect a schism within the kingdom between north and south, and Shakespeare may have used the rebellion by the Percies and the Welsh Glendower to reflect the antagonism between the Catholic north and west, site of a rising against Edward VI’s suppression of Catholicism in 1549, and the Protestant south and east, site of all but one of the burning of Protestants during Mary’s reign, in his own time.

RICHARD THE SECOND AND THE EARL OF ESSEX

Shakespeare’s Richard II did not merely reflect the struggles of the day, it figured in them. Shakespeare admired the dashing Earl of Essex and likened him not just to Henry V but to a “conquering Caesar” (Henry V, 5. Prol. 28). In 1593 he dedicated his Ovidian poem, Venus and Adonis, to Southampton, Essex’s chief ally and the lover and later husband of Essex’s cousin and ward. Both men were known as great frequenters of plays, and perhaps a performance of Shakespeare’s play gave Essex the idea that the aging Queen resembled Richard II.

Out of favor in 1599, Essex commissioned a history of the reign of Richard II, The First Part of the Life and Reign of King Henry IV, containing an account of Richard’s deposition. Sir John Hayward, the unhappy author, unwisely dedicated it to Essex as futuri temporis expectione, the heir apparent to the throne. A “mightily incensed” Elizabeth, who brooked no speculation about her successor, considered it “a seditious prelude to put into the people’s heads boldness and faction,” according to Essex’s advisor Sir Francis Bacon, and had the offending dedication removed. The first edition sold out, but the Privy Council, recognizing the parallels to Elizabeth’s increasingly unpopular regime—an inept and barren monarch, corrupt counselors, oppressive taxation, a mistreated and popular aristocrat whose opposition led to the monarch’s fall—suppressed a second edition.

The authorities had already recognized the seditious potential of the parallel. Although they licensed Shakespeare’s Richard II for publication in 1597, they demanded that the incendiary scene (4.1.154-318) in which the king is forced to surrender his crown be omitted. (The title page of the first printing of the play to include the scene, the 1608 quarto, proudly advertised that it contained the “deposing of King Richard.”) On February 6, 1601, Sir Charles Percy, a descendant of Shakespeare’s Hotspur who had served under Essex in Ireland, arranged for a performance of Shakespeare’s play the next day. He had to pay an extra forty shillings because Shakespeare’s company thought that “the play of King Richard to be so old and so long out of use as that they should have small or no company at it.” On the seventh, loudly applauded by Essex’s clique, Richard II was revived at the Globe. The next day Essex and his men staged their abortive coup.

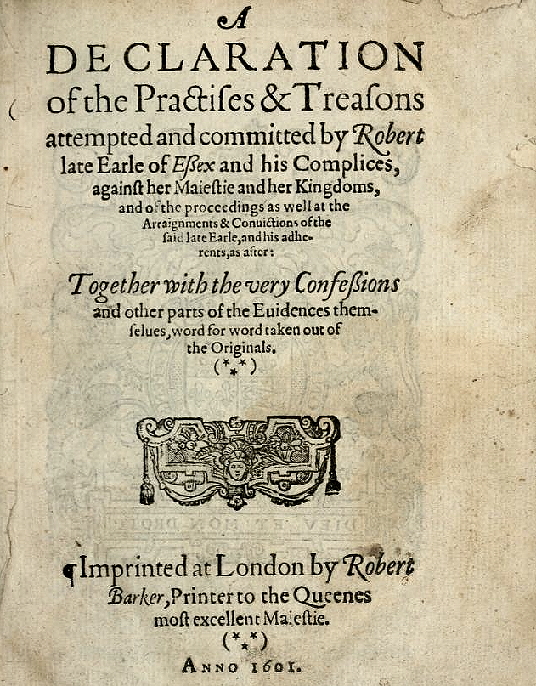

To Essex and his followers, as well as to the authorities, commissioning the performance was part of the conspiracy, an attempt to influence the Queen’s subjects into joining their revolt. Remembering the extra forty shillings, Francis Bacon wrote of Percy in “A Declaration of the … Treasons by Robert late Earle of Essex,” “So earnest he was to satisfy his eyes with the sight of that tragedy which he thought soon after his lord should bring from the stage to the state, but that God turned it upon their own heads.”

Elizabeth would have been especially sensitive to the charges Shakespeare leveled at Richard II. To finance his foreign wars, Richard says,

We are enforced to farm our royal realm. . . If that come short Our substitutes at home shall have blank charters. (1.4.45, 47-8)

“To farm the realm” was to lease the collection of taxes and duties to favorites in return for a fixed rent; “blank charters” were levies authorized by the king with the names and amounts left blank, so that “when they shall know what men are rich, ” Richard’s tax collectors could “subscribe them for large sums of gold” (4950). In choric speeches Ross and Willoughby ascribe Richard’s unpopularity to such measures, adding “benevolences,” an ironic term for forced loans, to their list:

The commons hath he pilled with grievous taxes And quite lost their hearts. The nobles hath he fined For ancient quarrels and quite lost their hearts. And daily new exactions are devised, As blanks, benevolences, and I wot not what. . . The Earl of Wiltshire hath the realm in farm. (2.1.246-50, 256)

Under her Lord Treasurer Burghley, Elizabeth revived the practice of farming the realm, starting with the duties on wine and beer in 1568 and swiftly extending it to all customs on imports into London and import and export duties everywhere. She also resorted more and more frequently to forced loans, raising £330,600 in 1569, 1588, 1590, 1597, and 1601, three-quarters of it without paying any interest. A naked exercise of royal prerogative, the forced loans were deeply resented.

Just as unpopular were the monopolies, a kind of excise tax which the Queen licensed her favorites and their dependents to collect. Many monopolies were designed simply to corner the market in a commodity for their holders or to enable them to extort payments from tradesmen for carrying out their normal business. Levied on all sorts of staples like salt, starch, glass, and tin, monopolies mushroomed during Elizabeth’s last decades. The Queen’s last great favorite, Sir Walter Ralegh, for example, enjoyed monopolies on tin, playing cards, and the licensing of alehouses. Bitter resentment at the abuse of monopolies broke out in Parliament in 1597 and 1601. In 1601 a listing of the monopolies created since 1597 caused one young Member, William Hakewill, to interrupt, “Is not bread there?” and to add, “If order be not taken for these, bread will be there before the next Parliament.” The Member for Barnstaple dubbed the monopolists the “bloodsuckers of the commonwealth.” Elizabeth finally gave in. In a speech before Parliament, she canceled twelve monopolies overnight, halting others in the works, and making monopolists answerable to the common law courts. Shakespeare may very well have had the monopolies in mind when the Gardener in Richard II promises,

I will go root away The noisome weeds which without profit suck The soil’s fertility from wholesome flowers. (3.4.379)

After Essex’s coup one of Shakespeare’s fellow shareholders in the company was called before the Privy Council to explain their role in the plot. The unfortunate Hayward was haled before the Star Chamber and then tossed in the Tower, there to remain until the old queen died. At Essex’s trial the prosecution stressed that Essex had frequently attended and warmly applauded Shakespeare’s play. The prosecutor, Sir Edward Coke, argued that the Queen “should not have long lived after she had been in [Essex’s] power. Note but the precedents of former ages, how long lived Richard the Second after he was surprised in the same manner? The pretence was alike for the removing of certain counsellors, but yet shortly after it cost him his life.”

Nor was that fact lost upon the aged Queen herself. In her privy chamber with her Keeper of the Records of the Tower, months after she reluctantly sent Essex to the block, “her majesty fell upon the reign of King Richard II, saying ’I am Richard II, know ye not that?’” The keeper caught her allusion: “Such a wicked imagination was determined and attempted by a man, the most adorned creature that ever your majesty made,” he said, referring to the ungrateful Essex. “He that will forget God, will also forget his benefactor,” the Queen replied; “this tragedy was played 40 times in open streets and houses.” Even the queen herself feared the power of the stage. Back to top